by Jeanne Elizabeth Daniel, Data Scientist, Stubben Edge

Today, there is 1 person over the age of 65 for every 3 people of working age in the United Kingdom. By 2050, this ratio is expected to shift to 1 person for roughly every 2 people of working age. This forecast is based on currently observed declining fertility rates, a slow-down in increases in life expectancy over the past decade, and assumptions on future net migration, all made by the Office of National Statistics (ONS).

An ageing population poses several challenges to society, as well as the life insurance industry. Life insurance offers a list of products to consumers such as whole life insurance or term life insurance, which guarantees a payout in the event of death, for one’s whole life or for the term covered, respectively. The consumption of life insurance products is typically triggered after life events such as marriage, child, or the purchase of a home.

In this paper, we present the various factors that are expected to influence future demographics in the UK, as well as their implications for the life insurance industry.

Declining fertility rates in the UK, supplemented by positive net migration, means that the size of the workforce will remain constant for the next few decades, while the number of people over 65 will continue to increase. We expect this to pose a liquidity risk for life insurance firms, who rely on a healthy base of young contributors for income while paying out an increasing number of death benefits for a growing elderly population.

Further, improvements in life expectancy over the past decade seems to be confined to those living in the least deprived areas in the UK, while those living in the most deprived areas saw no significant improvement. If this gap continues to widen, insurers would need to somehow price in the risk posed by lower life expectancy amongst the less affluent. This may be achieved by raising premiums across the board, but doing so means risking unhealthy churn.

Lastly, we believe that the higher concentration of elderly people present a catastrophic mortality risk, and will require a greater diversification strategy to hedge against the accumulation of losses.

Together these factors influencing demographic changes present a perfect storm, set to make landfall around 2050. Insurers would be forced to keep premiums low to continue to attract young consumers, in a market where economic growth is stagnant because the workforce is no longer growing, all the while paying out an increasing number of death benefits for ageing boomers. We expect that, without intervention, the life insurance industry will become less profitable over time.

Declining Fertility Rates

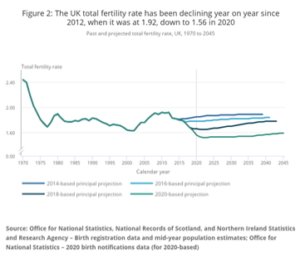

Fertility rates have been declining in the UK and its peer countries in Northern and Western Europe ever since the financial crisis of 2008. Between 2008 and 2018, total fertility rates in the UK have dropped from 1.91 to 1.56, while they were still rising between 2000 and 2008 (Source).

Economic uncertainty, along with the affordability and opportunity cost of having children (i.e. negative impact on career), has resulted in delayed childbearing and fewer children for women who chose to have them. According to the ONS, for the first time ever, more than half the women born in 1990 were still childless by the age of 30.

The 2020 lockdown in response to the COVID-19 pandemic was widely expected to result in a baby boom, but quite the opposite happened. According to the ONS report on provisional births in England and Wales for 2020 and Q1 2021, there were steep decreases in monthly fertility rates in December 2020 and January 2021, when compared to the same months a year ago, 8.1% and 10.2%, respectively. If there was a baby boom in lockdown, we would have expected to see an uptick in these months. Only March 2021 saw a slight increase of 1.7%, compared to March 2020, which corresponds with lockdown restrictions relaxing in the summer of 2020.

The ONS assembled an expert advisory panel to discuss short term and long term fertility trends in the UK to assist with its 2020-based interim national population projections. The recommendations from the panel were:

- an average of 1.53 total fertility rate (TFR) in the short-term (2024)

- an average of 1.59 TFR in the long-term (2044),

- age specific fertility rates (ASFRs) for age groups under 30 years will continue to decrease,

- while ASFRs for women aged 40 years and over continue to rise.

Although it is clear that total fertility rates in the UK are in a long-running decline, the panel elected for an optimistic view that the fertility rate in the UK will remain stable at its current rate for the next few decades. However, we believe that the current trend will continue and that is unlikely to change unless the factors influencing it changes. While economic uncertainty, and the high opportunity and financial cost of childbearing continues, total fertility rates are likely to continue to decline in the UK.

Stagnation in Life Expectancy Gains

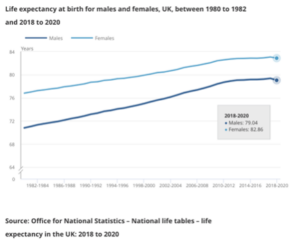

Over the past decade, improvements in period life expectancy in the UK have stagnated. This came as a surprise to many, who expected the rates of improvement to life expectancy from the 40 years prior to continue. In 2018-2020, life expectancy at birth was estimated at 79.04 years for men and 82.86 years for women, a scarce 1.32% and 0.95% increase over the same period a decade prior, respectively. This period also recorded the first decline in life expectancy at birth for men from the previous non-overlapping period of 2015-2017.

The introduction of public health measures such as childhood immunisations, universal health care, medical advances in treating adult diseases such as heart disease and cancer, and lifestyle changes including a decline in smoking all contributed to improvements in life expectancy at all ages. Therefore, the slowdown in improvements in life expectancy from 2010 onwards was unexpected. Many have speculated the reasons for this slowdown in the UK, be it the increasing prevalence of lifestyle diseases or that we are simply approaching the natural limit of human life expectancy.

A study by the ONS on changing trends in mortality by leading causes for England and Wales found that for males and females under 75 years, between 2011 and 2018 there was a slowdown in mortality improvements for heart disease, cerebrovascular diseases (such as strokes and aneurysms), cancer of the colon, sigmoid, rectum and anus, and breast cancer (for females only). Many of these diseases have lifestyle as a risk factor.

However, it is clear that there is still room for improvement in human life expectancy. According to Worldometer, the United Kingdom ranks only 29th in the world for life expectancy for both sexes (Source).

The period of stagnation in life expectancy gains coincided with austerity measures introduced in 2010, which saw cutbacks to the National Health Service, public health and social care spending. A study by the University of York estimated that the constraints on health and social care spending during the period of 2010-2014 resulted in 57,550 more deaths than would have been expected had the growth in spending followed trends before 2010 (Source). However, other European countries that did not introduce austerity measures, such as Germany, saw a similar slowdown in life expectancy, while other countries that did introduce austerity measures, such as Spain, saw an improvement in life expectancy. (Source).

The slowdown could also be linked to the wealth gap. According to the ONS report (Report) on health inequalities on data up to 2019, females and males living in the least deprived areas of England saw a significant increase in life expectancy between non-overlapping periods 2014 to 2016 and 2017 to 2019; while those living in the most deprived areas saw no significant changes. Similarly, the ONS report on household income inequality found that in the 10-year period leading up to financial year ending (FYE) 2020, income inequality increased by an average of 0.2 percentage points per year to 36.3%, as measured by the Gini coefficient. This was the highest level of income inequality since FYE 2010, but was lower than levels reported during the economic downturn of FYE 2008.

A panel of experts on mortality in the UK was formed to discuss views on future mortality rates, both to assess the short term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and to advise on target mortality improvements by 2044 by age and sex. The recommendations from the panel were:

- Annual rates of mortality improvement are assumed to converge to 1.2% for ages 0 to 90 years by 2045 and remain constant thereafter

- For those between the ages of 91 and 109, the annual rate of mortality improvement is set to decline linearly from 1.2% to 0% between ages 91 and 109 years

- For those aged above 110, no improvement in life expectancy is expected

- Thus, period life expectancy at birth for UK males is projected to increase from 78.4 years in 2020 to 82.2 years in 2045; for UK females, period life expectancy at birth is projected to increase from 82.4 years in 2020 to 85.3 years in 2045.

- Assume that the increases in mortality rates experienced in 2020 for those aged 30 years and over will be largely reversed by 2022.

Life expectancy is a lagging variable, and should be treated with caution. Much like fertility rates, it is unlikely that the current forecasted life expectancy would be maintained over the next 30 years. Improvements in life expectancy in the UK had been slowing down even since before the COVID-19 pandemic, a trend which may continue. Further, the fact that improvements in life expectancy have also been found to be most pronounced in the least deprived areas in the UK over the past decade, while the most deprived areas have no significant improvement, should certainly be noted. If inequality is the main driver for the stagnation in improvements in life expectancy, we may continue to see a slowdown or even a decline while income inequality becomes more pervasive.

Net Migration Assumptions

Besides fertility rates and life expectancy, the other factor that influences long-term population trends is net migration. The ONS projects net international migration in the UK is projected to reach an annual average of 205,000 from mid-2027 onwards (the long-term assumption). Before then, net migration is expected to average 232,000 each year. The age and sex distribution of the net migration population is assumed to be the average derived the past 5 years of historical international migration data (Source).

Net migration is expected to be the main driver of population growth over the next few decades, which would otherwise have contracted given that deaths are predicted to outnumber births from 2025 onwards.

Long-term Population Projections

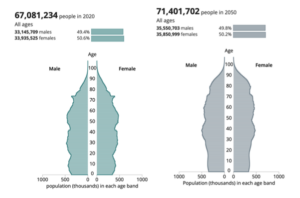

Provided the assumptions on fertility, life expectancy and net migration hold for the next few decades, the ONS has projected the population to increase by 6.4% by 2050, from 65 million in 2020 to 71.4 million people in 2050.

One consequence of the declining fertility rates and increasing life expectancy is that there will be an increasing number of older people whose growth will outpace that of the whole population. Between 2020 and 2050, the number of people 65 and over will grow from 12.5 million to 17.9 million people (a 43.1% increase). Meanwhile, the working-age population’s growth will lag the growth of the overall population. The number of people between 15-64 (generally considered “working age”) will increase from 42.6 million in 2020 to 42.8 million in 2050 (a 0.5% increase). The number of children and adolescents (under 15 years old) is set to decrease from almost 12 million in 2020 to 10.7 million in 2050 (a 10.7% decrease).

The demographic burden on the working-age population, measured as the ratio of total dependents (under 15 and 65 and over) to working age people (15-64), is set to increase from 57.5% to 66.8%. When we split this among the old and the young, we see that the old-age dependency ratio is set to increase from 29.4% to 41.8%, while young-age dependency is set to decrease from 28.1% to 25.0%.

Note that this projection is based on the fertility assumptions, life expectancy, and net migration assumptions described in the previous sections. To summarise the factors that are expected to influence the demographics in the United Kingdom:

- Fertility rates are expected to be maintained at an average of 1.59.

- Improvements in life expectancy have stagnated in the past decade, and may be linked to increased prevalence of lifestyle disease, increases in inequality and/or austerity measures introduced post-2008 recession.

- Life expectancy is expected to continue to improve and largely reverse the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic for those over 30.

- The working age population is expected to be kept stable through positive net migration.

- The elderly population is expected to grow 43% between 2020 and 2050.

- The number of children and adolescents is expected to decrease by 10.7% between 2020 and 2050.

- Old-age dependency is expected to increase, while young-age dependency is set to decrease.

- The total population is expected to increase 6.4% by 2050.

Life Insurance

When a consumer purchases a whole life insurance product, they are guaranteed a death benefit paid to their intended beneficiaries, regardless of when death occurs. This is the most sought after form of life insurance, as it provides a certainty for the consumer that their affairs would be taken care of in the event of their death, and typically is very affordable when purchased early in life. For this type of insurance, a 30-year old consumer, expected to live until 80 years of age, pays on average £200 per month for 50 years (a total sum of £120k) to get a death benefit of c£500k.

In the initial phase of a life insurance policy, the insurance company leverages their huge balance sheet to front the principal investment (£120k) it expects to receive in premiums over the next 50 years or so from the healthy 30 year old. This principal is invested with an investment horizon of about 40 years, where it is expected to grow to at least cover the agreed-upon payout benefit of £500k. As the insurance product approaches maturity, the investments are moved from illiquid to liquid assets. Given the low interest rates environment, there is a high opportunity cost to converting investments from high-yield bonds, for example, to cash. Therefore, revenue from premiums are also used to pay out insurance claims such as death benefits. Any growth above the payout benefit and expenses can be pocketed and contribute to the bottom line of the insurer. If the insurer has to pay out the death benefit before the investment has reached maturity, the insurer could stand to make a loss.

An insurance company’s revenues typically come from premiums and investment income, while its expenses arise from claims and a variety of other sources. In general, the main risk for a firm is that revenues are unable to cover expenses. We discuss three scenarios in which the changing population structure may threaten the solvency of life insurers.

Liquidity Risk

Liquidity risk may be defined as the risk that an insurance firm, though solvent, either has insufficient cash available to meet its obligations as they fall due, or can only secure cash at an excessive premium. If liquid resources are not already available to meet a financial commitment as it falls due, liquid funds will need to be borrowed and/or illiquid assets sold in order to meet the commitment. Losses would arise from the interest on borrowings and from any discount that would need to be offered to realise assets. In the worst case scenario, a life insurer may not be able to meet its commitments.

In the UK, the working age population is expected to stay constant between 2020 and 2050, while the number of people over 65 increases by 43%. The number of children and adolescents under 15 years of age is expected to decline by 10.7%. This means that the old-age dependency ratio is set to increase dramatically, while the young-age dependency ratio is set to decrease, perhaps less dramatically. We expect this to have a material effect on the profitability of life insurance firms, as demand and thus revenue would cease to increase while insurers have growing expenses due to an increasing number of death benefit payouts. We highlight the reasons for this impact below.

Firstly, a higher demographic burden (the total number of dependents vs the number of working-age people) has been shown to have a negative effect on the insurance market. The working-age population is expected to stay stable over the next few decades, while the proportion of young dependents will decrease over time, and the number of elderly dependents will increase over time (at a much higher rate). This will result in a net higher demographic burden. Over the long term, a higher demographic burden slows down economic growth, which in turn reduces savings, and therefore consumers have limited opportunities and spend less on insurance (Source).

Secondly, a decline in fertility may result in a decline in uptake for life insurance.

The young-age dependency ratio has been shown to positively correlate with demand for life insurance in developed countries (Source). This is because having children as dependents provide a strong motivation for purchasing life insurance. The predicted decline in fertility may result in a reduction in demand for life insurance products.

Lastly, a non-increasing working-age base may mean that insurers would have to raise premiums to preserve a growing income, whilst managing the growing expenses of paying death benefits. Increasing premiums may result in a smaller uptake of life insurance among the younger population, thus reducing the supporting base that life insurance relies on.

This would compound the long-term negative effect of a higher demographic burden and the declining fertility rate, which together may threaten liquidity amongst life insurers over time.

Poverty Premium Risk

The poverty premium in insurance means that low-income households pay more for insurance or are prevented from accessing the protection that insurance can provide. These households are often those who would benefit the most from the protection that insurance provides. If life expectancy continues to only improve for the most affluent, and the wealth gap continues to widen, we may see a future where increasing poverty levels draws life expectancy down.

Insurers would need to somehow price in the risk posed by stagnating or declining life expectancy among less affluent (poverty premium) by raising premiums across the board. This may price out the poorest customers, while wealthier customers may choose to rather rely on their own savings as the benefit offered by life insurance decreases. This could mean that the pool of customers for life insurers could shrink to only the middle class.

Catastrophic Mortality Risk

A catastrophic mortality event is characterised by a sudden and concentrated increase in mortality and as such presents a major risk to life insurers. These events include natural disasters, war, pandemics, terrorist attacks and accidents such as plane crashes. Elderly people are more vulnerable in such events, as they often have decreased mobility, are more susceptible to extreme weather, and have weakened immune systems.

A higher concentration of elderly people, as predicted in the coming decades, will concentrate the risk and potentially increase the severity of catastrophic mortality events. To mitigate this risk, insurers would have to diversify their risk profiles, by ensuring they have a good mix of all ages, such that the young population concentration offsets the older population concentration, in the event of a catastrophe.

Conclusion

Decreasing fertility in the United Kingdom may carry a two-fold long-term risk for life-insurers. Firstly, fewer young dependents means less motivation for taking out a life insurance policy primarily designed for protecting one’s dependents in the case of death. Secondly, declining fertility rates will have a lasting impact on the shape of the population, resulting in a higher concentration of elderly people and fewer people joining the workforce. A higher concentration of elderly people may increase the severity of catastrophic mortality events.

Over the past decade, life expectancy ceased to improve for those living in the most-deprived areas of the UK, while those living in the least-deprived still saw improvements. As inequality grows, the gap between life expectancy for the poorest and richest may grow as well. Insuring the longevity of the poorest would carry a higher risk, as such, life insurers would need to raise premiums across the board which may further shrink the consumer base. In the end, life insurers will increasingly compete for the shrinking pool of healthy young consumers seeking health insurance to diversify their portfolio. This will put downward pressure on premiums which insurers would otherwise be desperate to raise to account for growing expenses due to an ageing population.

The life insurance industry as a whole will become less profitable over the next few decades, as the market shrinks due to stagnating growth and decreased demand. Insurers would have to raise premiums or liquidate assets more readily to compensate for the decline in revenue from premiums.

To survive this perfect storm, insurers would have to diversify their revenue streams, improve their risk modelling to minimise losses, attract a healthy support base, and increase the uptake of insurance within the working-age population.